National Security

(How the CIA ran a “billion dollar spy” in Moscow?)

By David E. Hoffman

Trần Anh Phúc dịch

Lê Hồng Hiệp hiệu đính

The Washington Post

July 04/2015.

An identity card created by the CIA in an attempt to replicate

Adolf Tolkachev’s building pass to facilitate removing secret

documents from his Soviet military institute. Despite much

effort, the plan worked only briefly in the summer of 1982.

(Courtesy of H. Keith Melton and the Melton Archive/

From the book “The Billion Dollar Spy”)

The spy had vanished.

He was the most successful and valued agent the United States had run inside the Soviet Union in two decades. His documents and drawings had unlocked the secrets of Soviet radars and weapons research years into the future. He had smuggled circuit boards and blueprints out of his military laboratory. His espionage put the United States in position to dominate the skies in aerial combat and confirmed the vulnerability of Soviet air defenses — showing that American cruise missiles and strategic bombers could fly under the radar.

In the late autumn and early winter of 1982, the CIA lost touch with him. Five scheduled meetings were missed. KGB surveillance on the street was overwhelming. Even the “deep cover” officers of the CIA’s Moscow station, invisible to the KGB, could not break through.

On the evening of Dec. 7, the next scheduled meeting date, the future of the operation was put in the hands of Bill Plunkert. After a stint as a Navy aviator, Plunkert had joined the CIA and trained as a clandestine operations officer. He was in his mid-30s, 6-foot-2, and had arrived at the Moscow station in the summer. His mission was to give the slip to the KGB and make contact.

That evening, around the dinner hour, Plunkert and his wife, along with the CIA station chief and his wife, walked out of the U.S. Embassy to the parking lot, under constant watch by uniformed militiamen who reported to the KGB. They got into a car, the station chief driving. Plunkert sat next to him in the front seat. Their wives were in the back, holding a large birthday cake.

[ CIA memo describing sensitive Soviet military documents delivered in bulk by Tolkachev ]

Espionage is the art of illusion. Tonight, Plunkert was the illusionist. Under his street clothes, he wore a second layer that would be typical for an old Russian man. The birthday cake was fake, with a top that looked like a cake but concealed a device underneath, created by the CIA’s technical operations wizards, called the jack-in-the-box. The CIA knew that KGB surveillance teams almost always followed a car from behind and rarely pulled alongside. It was possible for a car carrying a CIA officer to slip around a corner or two, momentarily out of view. In that brief interval, the CIA case officer could jump out of the car and disappear. At the same time, the jack-in-the-box would spring erect, a pop-up that looked, in outline, like the head and torso of the case officer who had just jumped out.

The device had not been used before in Moscow, but the CIA had grown desperate as weeks went by. Plunkert took off his American street clothes. Wearing a full face mask and eyeglasses, he was now disguised as an old Russian man. At a distance, the KGB was trailing them. It was 7 p.m., well after nightfall.

The car turned a corner. Plunkert swung open the passenger door and jumped out. At the same moment, one of the wives placed the birthday cake on the front passenger seat. With a crisp whack, the top of the cake flung open, and a head and torso snapped into position. The car accelerated.

Outside, Plunkert took four steps on the sidewalk. On his fifth step, the KGB chase car rounded the corner. The headlights caught an old Russian man on the sidewalk. The KGB ignored him and sped off in pursuit of the car.

The jack-in-the-box had worked.

Agent who wanted revenge

In the early years of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, the Central Intelligence Agency harbored an uncomfortable secret about itself. The CIA had never really gained an espionage foothold on the streets of Moscow. Recruiting spies there was just too dangerous for any Soviet citizen or official they might enlist. The recruitment process itself, from the first moment a possible spy was identified and approached, was filled with risk of discovery by the KGB, and, if caught spying, an agent would face certain death. A few agents who volunteered or were recruited by the CIA outside the Soviet Union continued to report securely once they returned home. But for the most part, the CIA did not lure agents into spying in the heart of darkness.

A painting of Tolkachev, by Kathy Krantz Fieramosca,

hangs at CIA headquarters. (Kathy Krantz Fieramosca/

From the book “The Billion Dollar Spy”)

Then came an espionage operation that turned the tide. The agent was Adolf Tolkachev, an engineer and specialist in airborne radar who worked deep inside the Soviet military establishment. Over six years, Tolkachev met with CIA officers 21 times on the streets of Moscow, a city swarming with KGB surveillance.

Tolkachev’s story is detailed in 944 pages of previously secret CIA cables about the operation that were declassified without condition for the forthcoming book “The Billion Dollar Spy.” The CIA did not review the book before publication. The documents and interviews with participants offer a remarkably detailed picture of how espionage was conducted in Moscow during some of the most tense years of the Cold War.

Tolkachev was driven by a desire to avenge history. His wife’s mother was executed and her father sent to labor camps during Joseph Stalin’s Great Terror of the 1930s. He also described himself as disillusioned with communism and “a dissident at heart.” He wanted to strike back at the Soviet system and did so by betraying its military secrets to the United States. His CIA case officers often observed that he seemed determined to cause the maximum damage possible to the Soviet Union, despite the risks. The punishment for treason was execution. Tolkachev didn’t want to die at the hands of the KGB. He asked for and got a suicide pill from the CIA to use if he was caught.

[CIA memo on the first phone call with Tolkachev, a Soviet engineer and agency asset]

The Air Force estimated at one point in the operation that Tolkachev’s espionage had saved the United States $2 billion in weapons research and development. Tolkachev smuggled most of the secret documents out of his office at the lunch hour hidden in his overcoat and photographed them using a Pentax 35mm camera clamped to a chair in his apartment. In return, Tolkachev asked the CIA for money, mostly as a sign of respect. There wasn’t much to buy in shortage-plagued Moscow. He also wanted albums of Western music — the Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Uriah Heep and others — for his teenage son.

Tolkachev became one of the CIA’s most productive agents of the Cold War. Yet little is known about the operation — a coming-of-age for the CIA, when it accomplished what was long thought unattainable: personally meeting a spy under the nose of the KGB.

Eluding the KGB

The Moscow station was a secure room the size of a boxcar nestled inside the U.S. Embassy. Case officers huddled at small desks, scrutinized maps on the wall scattered with red push pins to mark dangerous KGB hot spots and meticulously plotted every move.

David Rolph, Tolkachev’s second case officer.

(Courtesy of David Rolph/ From the book “The Billion Dollar Spy”)

David Rolph, on his first CIA tour, took over as Tolkachev’s case officer in 1980. Late in the afternoon of Oct. 14, he walked out of the station and went home. An hour later, he returned to the embassy gate with his wife, dressed as if going to a dinner party. A Soviet militiaman, standing guard, noticed them enter the building. Rolph and his wife navigated the narrow corridors to one of the apartments, and pushed open a door already ajar. The apartment belonged to the deputy technical operations officer in the Moscow station, an espionage jack-of-all-trades who helped case officers with equipment and concealments, from sophisticated radio scanners to fake logs.

The deputy tech motioned wordlessly to Rolph. The men were approximately the same height and physique. In silence, Rolph began to transform himself to look like his host, known as identity transfer. The deputy tech had long, messy hair. Rolph put on a wig with long, messy hair. The deputy had a full beard. Rolph put on a full beard. The deputy tech helped Rolph adjust and secure the disguise, then fitted him with a radio scanner, antenna and earpiece to monitor KGB transmissions on the street.

From the doorway, Rolph heard a voice. It was the chief tech officer, who had just arrived and was deliberately speaking loudly, assuming they were being overheard by KGB listening devices. “Hey, are we going to go and check out that new machine shop?” the chief asked. The real deputy replied, aloud, “Great! Let’s go.”

But the real deputy did not leave the apartment. The man who left the apartment looking like him was Rolph. The real deputy pulled up a chair and settled in for a long wait. Rolph’s wife, in her dinner dress, also sat down and would remain there for the next six hours. They could not utter a word, because the KGB might be listening.

The point of the identity transfer was to break through the embassy perimeter without being spotted. The KGB usually ignored the techs when they drove out of the compound in search of food, flowers or car parts in an old beige-and-green Volkswagen van. On this night, the van pulled out at dusk. The chief tech was at the wheel, Rolph in the passenger seat. The van windows were dirty. The militiamen just shrugged.

The Moscow gas station where Adolf Tolkachev made his first

approach to the CIA on Jan. 12, 1977.

(Courtesy of Valery Smychkov/From the book “The Billion Dollar Spy”)

Once on the street, the van took a slow, irregular course. In departing the embassy in disguise, Rolph’s goal was to evade the KGB, but over the next few hours he gradually unfolded a new approach, attempting to flush out the KGB. Ultimately, his mission was to “get black,” to completely shake the surveillance. But getting black required a long, exhausting test of nerves, even before he would get his first chance to look Tolkachev in the eyes.

On a surveillance detection run, the case officer had to be as agile as a ballet dancer, as confounding as a magician and as attentive as an air traffic controller. The van stopped at a flower shop, their first, routine cover stop, a pause to see if the KGB surveillance cars or foot patrol teams would get careless and stumble over themselves. Rolph sat still behind the dirty window of the van and saw nothing.

After another hour and a half of driving, Rolph began a mental countdown. The rule of thumb was to advance to the next stage only if he was 95 percent certain he was black. The reason was simple: He had the upper hand in the car. On foot and alone, he would be much more vulnerable. Rolph weighed what he had seen on the darkening streets. He was sure. He looked to the chief tech, who gave him a thumbs up. While the van was still moving, Rolph quickly slipped off the disguise and put it into a small sack on the floor. He grabbed the shopping bag that had been prepared for Tolkachev and put on a woolen coat. The van halted, briefly. Rolph slid out and walked briskly away.

Soon, on another broad avenue, he walked directly into a crowd waiting for one of the electric trolley buses that prowled Moscow’s major arteries. He scanned the trolley passengers, taking careful note of those who boarded with him. Then he abruptly stepped toward the door and jumped off at the next stop, watching to see who followed. No one.

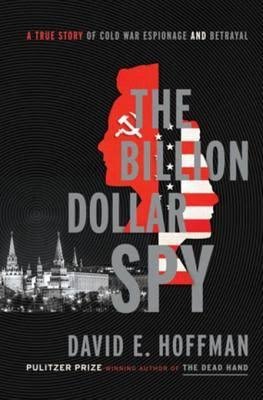

Book cover

On foot, he began the final stage. Rolph was physically fit, and his head was clear, but surveillance detection runs were grueling. The late autumn weather felt raw, moist and heavy. His mouth grew dry, but there was nowhere he could safely stop. The radio scanner was quiet but for the usual patter and static. At a small theater, Rolph pushed open the doors. This was his second cover stop. He checked out the posted schedule and notices on the wall. His goal was to force the KGB men to do something out of character, to slip, so that he could spot them before they could call in reinforcements. Rolph left the theater with tickets for a show he had no intention of attending. Rolph walked to an antiques store, far from his usual routines. Still nothing. Then he entered a nearby apartment building and started climbing the stairs. This was certain to trigger a KGB ambush; they could not allow him to disappear from sight in a multi-floor apartment building. In fact, Rolph had nowhere to go and knew not a soul who lived there. He was just trying to provoke the KGB. At a landing on the stairs, he sat down and waited. No one came running.

Rolph turned around. For 3 1/2 hours, the KGB had been nowhere in sight. Still, to make sure, he walked to a small park lined with benches. Rolph looked at his watch. He was 12 minutes from the meeting site.

Time to go. He was 100 percent sure. He rose from the bench.

Suddenly he was jolted by a squelch in his earpiece, then another and a third. They were loud, clearly from the KGB’s surveillance teams. He stood frozen, rigid, tense. The squelch could sometimes be used as a signal, from one KGB man to another. But the noise could also have been a ham-fisted operator who hit his button by mistake.

Rolph often repeated the words “when you’re black, you’re black.” In his mind, it meant that when you are black, you can do anything, because nobody is watching you.

Nothing. No sign of anyone in the park. Rolph let his shoulders drop and took a deep breath.

When you’re black, you’re black.

The meeting with the spy went perfectly. Tolkachev passed 25 rolls of film containing copies of top-secret documents. Rolph returned to the Volkswagen van, donned the beard and wig, and they drove back to the embassy. The guards didn’t give them a second glance. The gate opened. A little while later, the Soviet militiamen in the shack took note that David Rolph and his wife left the embassy dinner party for home.

David E. Hoffman

Adapted from David E. Hoffman’s “The Billion Dollar Spy: A True Story of Cold War Espionage and Betrayal,” published July 7 by Doubleday. A selection of declassified CIA cables from the Tolkachev operation are posted at davidehoffman.com.

David Emanuel Hoffman is an American writer and journalist, a contributing editor to The Washington Post. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 2010 for a book about the legacy of the nuclear arms race.

Journalism: Hoffman was born in Palo Alto, California and grew up in Delaware, where he attended the University of Delaware. He came to Washington D.C. in 1977 to work for the Capitol Hill News Service. As a member of the Washington bureau of the San Jose Mercury News, he covered Ronald Reagan's 1980 presidential campaign. In May 1982, he joined The Washington Post to help cover the Reagan White House. He also covered the first two years of the George H. W. Bush presidency. His White House coverage won three national journalism awards.

After reporting on the State Department, he became Jerusalem bureau chief for The Washington Post in 1992. After studying Russian at Oxford University, he began six years in Moscow. From 1995 to 2001, he served as Moscow bureau chief, and later as foreign editor and assistant managing editor for foreign news.

Hoffman's first book was published by PublicAffairs in 2002, The Oligarchs: Wealth and Power in the New Russia. He won the annual Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction in 2010 for his second book, The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and its Dangerous Legacy (Doubleday, 2009). The Prize citation termed it "a well documented narrative that examines the terrifying doomsday competition between two superpowers and how weapons of mass destruction still imperil humankind."

Bibliography:

- The Oligarchs: Wealth and Power in the New Russia (PublicAffairs, 2002), ISBN 978-1-58648-001-1

- The Dead Hand: The Untold Story of the Cold War Arms Race and its Dangerous Legacy (Doubleday, 2009), ISBN 978-0-385-52437-7

- The Billion Dollar Spy: A True Story of Cold War Espionage and Betrayal, New York, Doubleday, 2015, ISBN 978-0385537605 (about Adolf Tolkachev)

(From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia)

* * *

Vietnamese text, please click here

More on English topic, please click here

Main homepage: www.nuiansongtra.com

Trang Anh ngữ

Trang Anh ngữ